Put a tick on your tacking.

Reducing lost time through tacks can shave minutes from your time around the race track - By Tony Bull.

We all know that the boat that sails fastest around the race course is invariably the first boat home, but let's look at this from a different angle. The fastest boat can also be categorised as the yacht that sails slower for the least amount of time.

During the course of a race we do gybes, dips, peels, tacks, spinnaker hoists and drops. In each of these exercises the boat will be slowed and it would be common for at least 20 or so of these manoeuvres to occur in an average race. If we were to shave three to four seconds on average off these speed reductions then we would be over a minute further advanced on our finishing time and that could lift us a long way up the placings.

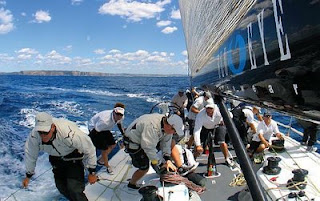

Dissecting a tackEveryone helps. Tacking a boat is usually a multi-person task (except for single handers); it can directly involve two people on a small day sailer or dinghy through to seven or eight on a maxi yacht. But all the crew have a role to play, from hiking hard to assist a speed build prior to tacking, using their weight and momentum from side to side to help roll tack and hiking hard again to help get the boat back to its target speeds.

Let's look at tacking a typical keelboat of 10-15m LOA. The setup will vary on smaller boats with fewer personnel compared to larger boats with grinding pedestals or powered winches, but the basics remain the same.

Headsail trimmersHeadsail trimmers and grinders are the most active crew in tacks. The manoeuvre begins with the person releasing the sheet. If that's your role, get in position at the winch and release as many turns of the sheet as you can without it starting to slip around the drum.

As the boat begins to turn, ease about an arm's length of sheet; this will ease the load off the sail and in the case of overlapping headsails will stop the sail backing on the spreaders.Once the sail begins to luff or ‘break', remove the remaining turns off the winch by lifting the sheet vertically, check the sheet runs smoothly without twists or knots and make your way to the newwindward rail.

The aim of the release person is to try and keep the flapping of the headsail to a minimum, as each flap will slow the boat down. But it is always better to err on the side of an early release than a late one.The next crew member involved will be tailing or hauling in the sheet. If that's your role, take as much slack sheet up as you can before the tack begins so there is less sheet to snap in once the manoeuvre begins. To this end I think the best position is to be centrally located in the boat, braced so both hands are free.The more sheet you can get in hand-overhand through the tack, the less that will have to be ground in. The sheet will usually only have two or three turns on the winch for easier tailing and to prevent over-rides.As the sheet is brought in and loads up, the grinder should take a couple of extra turns for purchase. The sail is then ground on but not all the way; leave a slight ease for the speed build out of the tack.The tailer can then hand the sheet over to the grinder to carry out the final trim, and hit the windward rail.

I prefer to have the primary trimmer doing the grinding rather than tailing as it means the tailer can peel off and go straight to the rail, rather than having to cross over with the grinder, and it does not necessitate two people being to leeward.

Mainsheet trimmerThe mainsheet hand as always should be a conduit between helm and trimmers. If that's your role, ease the mainsheet a little when calling for the speed build going into the tack, and the headsail trimmer will follow suit.

During the manoeuvre, ease a little more sheet or set the traveller down a touch to help rebuild the speed after the tack. Always have the sheet uncleated in your hand, in the event of the boat falling over onto its side if the helmsman comes out too low and overloads the rig, an all too common and all too slow occurrence.

Call the numbers as the boat begins to rebuild speed. Remember after a tack has been completed the boat speed will continue to drop, so wait until it starts building again before calling for the sheets to come on that final increment.

On the helmAs ever, the helmsman needs to concentrate completely. Don't look at where you are tacking to, other boats or the mark coming up. Concentrate on finding a nice piece of flat water to tack in and begin the speed build by bearing away a bit. Don't overdo it, just a couple of degrees will suffice, similar to a clean air start. Then begin the tack in a nice, smooth arc and once the sail breaks, accelerate the turn.

As the boat comes onto its new course do not over-steer, try and let the boat fall onto its new angle. It is very frustrating to see a steerer have to reverse his wheel or tiller to come back up to course after over-steering.Try to complete the tack with the minimal amount of rudder movement, because anangled rudder acts as a brake.

Practice makes perfectTacking a yacht in a congested piece of water, in close quarters with other boats or near a mark is a testing experience. It is still very important to tack well while remaining aware of the circumstances and not overreacting to other boats. Good peripheral vision and an awareness of how boats behave sets the top steerers apart from the average ones in these conditions.

Practice is important; every day's sailing provides a unique set of wind and waves. Go out and as part of your setup do lots of tacks. One good drill is to tack the boat every time you get up to target speed. Try a few quicker tacks and then a few slower ones and see which seems to work better for that day. If you do this for ten minutes you will have your tacks well and truly sorted for the race ahead.

Tony Bull's racing experience ranges from sportsboats to offshore racers. He runs the Bull Sails loft in Geelong.

We all know that the boat that sails fastest around the race course is invariably the first boat home, but let's look at this from a different angle. The fastest boat can also be categorised as the yacht that sails slower for the least amount of time.

During the course of a race we do gybes, dips, peels, tacks, spinnaker hoists and drops. In each of these exercises the boat will be slowed and it would be common for at least 20 or so of these manoeuvres to occur in an average race. If we were to shave three to four seconds on average off these speed reductions then we would be over a minute further advanced on our finishing time and that could lift us a long way up the placings.

Dissecting a tackEveryone helps. Tacking a boat is usually a multi-person task (except for single handers); it can directly involve two people on a small day sailer or dinghy through to seven or eight on a maxi yacht. But all the crew have a role to play, from hiking hard to assist a speed build prior to tacking, using their weight and momentum from side to side to help roll tack and hiking hard again to help get the boat back to its target speeds.

Let's look at tacking a typical keelboat of 10-15m LOA. The setup will vary on smaller boats with fewer personnel compared to larger boats with grinding pedestals or powered winches, but the basics remain the same.

Headsail trimmersHeadsail trimmers and grinders are the most active crew in tacks. The manoeuvre begins with the person releasing the sheet. If that's your role, get in position at the winch and release as many turns of the sheet as you can without it starting to slip around the drum.

As the boat begins to turn, ease about an arm's length of sheet; this will ease the load off the sail and in the case of overlapping headsails will stop the sail backing on the spreaders.Once the sail begins to luff or ‘break', remove the remaining turns off the winch by lifting the sheet vertically, check the sheet runs smoothly without twists or knots and make your way to the newwindward rail.

The aim of the release person is to try and keep the flapping of the headsail to a minimum, as each flap will slow the boat down. But it is always better to err on the side of an early release than a late one.The next crew member involved will be tailing or hauling in the sheet. If that's your role, take as much slack sheet up as you can before the tack begins so there is less sheet to snap in once the manoeuvre begins. To this end I think the best position is to be centrally located in the boat, braced so both hands are free.The more sheet you can get in hand-overhand through the tack, the less that will have to be ground in. The sheet will usually only have two or three turns on the winch for easier tailing and to prevent over-rides.As the sheet is brought in and loads up, the grinder should take a couple of extra turns for purchase. The sail is then ground on but not all the way; leave a slight ease for the speed build out of the tack.The tailer can then hand the sheet over to the grinder to carry out the final trim, and hit the windward rail.

I prefer to have the primary trimmer doing the grinding rather than tailing as it means the tailer can peel off and go straight to the rail, rather than having to cross over with the grinder, and it does not necessitate two people being to leeward.

Mainsheet trimmerThe mainsheet hand as always should be a conduit between helm and trimmers. If that's your role, ease the mainsheet a little when calling for the speed build going into the tack, and the headsail trimmer will follow suit.

During the manoeuvre, ease a little more sheet or set the traveller down a touch to help rebuild the speed after the tack. Always have the sheet uncleated in your hand, in the event of the boat falling over onto its side if the helmsman comes out too low and overloads the rig, an all too common and all too slow occurrence.

Call the numbers as the boat begins to rebuild speed. Remember after a tack has been completed the boat speed will continue to drop, so wait until it starts building again before calling for the sheets to come on that final increment.

On the helmAs ever, the helmsman needs to concentrate completely. Don't look at where you are tacking to, other boats or the mark coming up. Concentrate on finding a nice piece of flat water to tack in and begin the speed build by bearing away a bit. Don't overdo it, just a couple of degrees will suffice, similar to a clean air start. Then begin the tack in a nice, smooth arc and once the sail breaks, accelerate the turn.

As the boat comes onto its new course do not over-steer, try and let the boat fall onto its new angle. It is very frustrating to see a steerer have to reverse his wheel or tiller to come back up to course after over-steering.Try to complete the tack with the minimal amount of rudder movement, because anangled rudder acts as a brake.

Practice makes perfectTacking a yacht in a congested piece of water, in close quarters with other boats or near a mark is a testing experience. It is still very important to tack well while remaining aware of the circumstances and not overreacting to other boats. Good peripheral vision and an awareness of how boats behave sets the top steerers apart from the average ones in these conditions.

Practice is important; every day's sailing provides a unique set of wind and waves. Go out and as part of your setup do lots of tacks. One good drill is to tack the boat every time you get up to target speed. Try a few quicker tacks and then a few slower ones and see which seems to work better for that day. If you do this for ten minutes you will have your tacks well and truly sorted for the race ahead.

Tony Bull's racing experience ranges from sportsboats to offshore racers. He runs the Bull Sails loft in Geelong.

Comments

Post a Comment